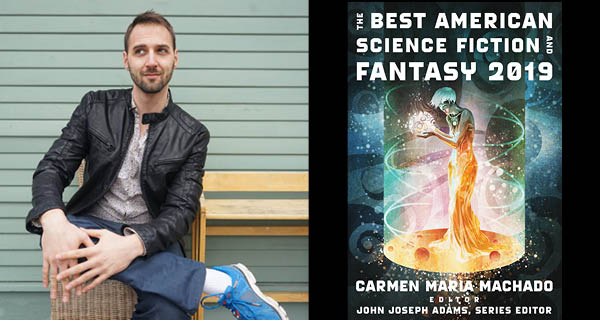

Now that applications for the Book Project are open (deadline: June 26), we thought we'd check in with Book Project and Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers' Workshop grad Ted McCombs, who was recently featured in Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2019.

Tell us about the Clarion experience. What was that like? How did it change your sense of yourself as a writer?

The Clarion Writers Workshop was such a watershed experience. I lucked out in the sheer level of talent my classmates brought, for one. There’s this eerie effect from sticking a bunch of highly engaged artists together for six weeks, where our collective energy takes on its own presence: as our instructor Lynda Barry put it, a sort of “muscularity” emerges in the work. But the people were just so fun, and the pace so mind-bogglingly crazy—you’re asked to write five completely original stories in six weeks—that I found myself taking risks I never would have dreamed of, to make my new friends laugh, or to see if I could surprise them, or to annoy Cory Doctorow, or simply because I didn’t have time to think of a safer idea. And then I saw the risks pay off! (Not all at once. Revision is a good friend of mine.)

It made me trust the bonkers side of me, because for all I’ve grown in craft and for all the great authors I’ve read, deep down I am a moody gay weirdo with obscure interests and an unreliable commitment to good taste, and maybe that’s the best of me.

One of the best pieces of advice we got was that workshop critiques are less helpful to the person whose story is being critiqued, than to the person writing the critique. By critiquing, you develop a sense of what you want from the story. You hone your aesthetic on others’ work—by engaging deeply with it, trying to understand what it’s doing, and deciding whether it succeeds according to criteria and principles you’re just now working out. That, more than anything, was what made Clarion so formative.

What’s the most important lesson you’ve learned about writing?

That a story has its own integrity, apart from the writer’s intentions for it. This is something you taught me, by the way. People can reflexively think of a literary work as something the writer pulls out of her head, just words and grammar, flatus vocis—that makes for disappointing work, I think. I’m afraid I get a little mystical when I think about “existence,” but you don’t have to: any story is helplessly entwined with the natural logics of its setting (or magical system!), the needs of character, the emotional experience of the author—all things that exist apart from the writer’s ingenuity, all things that push the story to lean in certain directions and check it in others. And the writer succeeds by following the story’s lead rather than forcing out preconceived plans. That doesn’t mean you can’t outline your novel, do all sorts of character backstory notes or other great prep work, and it doesn’t mean you throw out the writing rules or toolkits we learn in classes; but all that planning is only about understanding the terrain of the story, and all those tools are about being nimbler in going where it leads you.

You write both literary and speculative fiction. How do the genres speak to each other?

In her intro to this year’s Best American Science Fiction & Fantasy anthology, Carmen Maria Machado frames genre in terms of the question, What kind of pleasure does this story bring me? The idea is that genre, if it’s not treated too seriously, can be a useful way to connect to a reader from the beginning around a set of shared expectations for devices, effects, and pleasures they might find within. If you pick up a story called “Friend of my Youth,” by Nobel laureate Alice Munro, it’s likely you’re coming in with a different set of expectations than if that story is called “Red Dirt Witch,” and it’s by triple-Hugo-Award-winner N.K. Jemisin—although in both cases, your expectations will be smashed up quite pleasurably. Genre is about where you start.

If stories are all about the emotional experiences they evoke, I have an image of speculative fiction as a very particular tool, like a dentist’s scraper, designed to poke at those hard-to-reach, extremely particular crannies of the psyche. The ones obsessed with fate or time or souls, things so much larger than our individual experience that realist literary fiction can’t quite bite at them. Like, Proust has a lot of brilliant things to say about time and memory, but none of them reach the scale of Walter Miller’s Canticle for Liebowitz, or Cixin Liu’s Death’s End. One of the most relevant novels I read last year was Sandra Newman’s The Heavens, which, for me, captured that anxiety of watching the elation and hopefulness of the Obama era give way lumberingly to this disastrous, cruel social present. And I don’t think it could have succeeded as brilliantly as it does without its time-travelling Elizabethans.

Do you have readers you depend on these days?

Yes—a few from Clarion, and a few from the Lighthouse Book Project. It’s not just about their insight or craft acumen, but about establishing a degree of mutual trust and curiosity so that I can probe their reactions to a piece without losing my own bead on it. I like talking about anyone’s stories with these people, not just mine; I like their brains, I enjoy hearing how they think and discovering what they see that I don’t. That makes it easier when they’re chopping up my word-children and feeding them to me in pies. (That’s what a workshop is, you know.)

Is there a craft book you’d recommend?

Robin Black’s Crash Course. I did get a lot out of Robert Olen Butler’s From Where You Dream, which you recommended to me, especially in terms of the writing-as-dreaming process. And craft-wise, Joan Silber’s The Art of Time in Fiction has been impossibly useful. But Black’s book is the only one I’ve found that candidly treats the emotional experience of writing, which to me, is the foundation. Black does a brilliant job connecting concrete, vulnerable emotional questions to concrete craft issues that often turn out to be just as vulnerable. I’m in awe of it. And I’ve been profoundly helped by it.

What’s your favorite recent novel or collection?

I already mentioned The Heavens, so I get another. That’s only fair. I absolutely loved Eugene Vodolazkin’s Laurus—but that isn’t all that recent—and I’m thrilled by what Carmen Machado has done with In the Dream House—but that isn’t technically a novel. So I’ll say Exhalation, a collection of Ted Chiang’s recent short science fiction stories and novellas. I catch myself still thinking about the title story, months later. And I’m blown away by how Chiang uses plot and theme together as a kind of philosophical engine, letting Chiang play with the ideas he finds so fascinating, while pulling the reader in with his characters and the striking, oddball beauties he discovers.

Theodore McCombs is a writer in San Diego. His fiction and essays have appeared in Best American Science Fiction & Fantasy 2019, Guernica, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Lightspeed Magazine, Nightmare Magazine, Lit Hub, Electric Literature, and Beneath Ceaseless Skies, among others. He is a 2017 graduate of the Clarion Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers Workshop and a Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA) member. He co-edits and blogs about speculative literature for Fiction Unbound, and tweets as @mrbruff.