A few weeks ago I asked my husband, a former librarian, if it was okay to bring a library book backpacking.

"Not if you're the one doing it."

He wasn't being cruel; I'm notoriously hard on books. Every book on our shelves that I've read is marked in some unique way: torn and crinkled pages, food stains, coffee rings, waterlog.

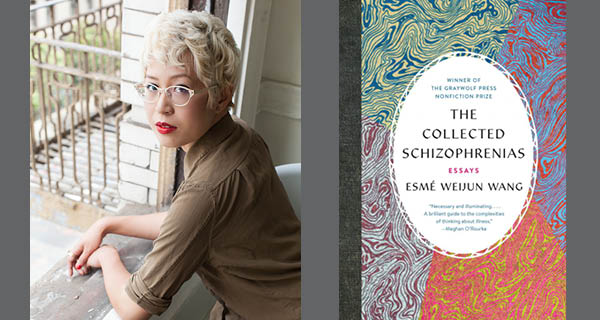

Regardless, I brought with me the library's copy of The Collected Schizophrenias, by Esmé Weijun Wang. Despite having sealed it in a gallon-sized ziplock, it returned completely soaked.

Before the Lexapro, this would have sent me into a complete tailspin. Beyond knowing that I'm awful at keeping books in good shape (true), I would have been certain that this meant there was something deeply wrong with me (probably untrue), so wrong that I'd feel physically ill. That my tendency towards mess and minor damage meant that my husband should leave me for someone better, that my bosses should fire me, and that, truly and deeply, I was unlovable.

The essays that make up The Collected Schizophrenias follow Wang's long struggle with mental and physical illness. First diagnosed with bipolar disorder, her illness is eventually classified as schizoaffective disorder. In addition to manias that make her certain she is dead (Cotard's delusion) or that her loved ones have been replaced by imposters (Capgras delusion), Wang also suffers from PTSD and late-stage Lyme disease, which may or may not be related to her schizoaffective disorder.

Since starting The Collected Schizophrenias, I've found myself describing my own mental health in Wang's captivating cadence. While I'm totally aware that the depression and anxiety that run in my family is nothing compared to the psychosis that makes Wang's reality unstable, her prose is so clear in its honesty, so quietly individual, that a reader might start to think in Wang's voice without even noticing it.

After learning that her mental condition is medication-resistant, Wang in desperation asks for an ECT (electroconvulsive therapy) consultation. Once a fashion blogger, Wang is careful and conscious about what she wears. Sometimes she'll use fashion to present as high functioning, but the morning of the consultation she wears a white v-neck shirt and black pants, partially because she'd lost so much weight due to illness that most of her Marc Jacobs dresses no longer fit. But mostly she dresses this way to strike a very particular balance: her clothing here is meant to communicate that she is "crazy" enough to need ECT, but not enough of a mess to need hospitalization.

For Wang, this balance is part of the language of illness. Along with an impossible litany of acronyms (ECT, SSRIs, NAMI, CT, TT, MTHFR, DSM, HMOs, SCID, MDD, LLMD, POTs, SUDs, etc), Wang's medical world is a shifting and sliding world of definitions, diagnoses, and believability. Her understanding of her own manias shifts as the DSM-5 refines the definition of schizoaffective disorder from the DSM-4. One doctor thinks her Lyme disease may affect or even be the cause of her neurological disorders while another doctor doesn't even believe she has late-stage Lyme disease (a disease so varied in its symptoms and so difficult to pin down with testing that the CDC does not recognize it a diagnosis). In the brief periods that she's institutionalized, her nurses don't believe she graduated from Stanford. She is always negotiating (writing seems to serve this function for her) a space between what is certain and uncertain, what is believable and what is real.

At one point, Wang explores how she should even refer to herself:

"In my peer-education courses, I was taught to say that I am a person with schizoaffective disorder. 'Person-first language' suggests that there is a person in there somewhere without the delusions and the rambling and the catatonia.

But what if there isn't? What happens if I see my disordered mind as a fundamental part of who I am? It has, in fact, shaped the way I experience life."

And later:

"There might be something comforting about the notion that there is, deep down, an impeccable self without disorder, and that if I try hard enough, I can reach that unblemished self.

But there may be no impeccable self to reach, and if I continue to struggle towards one, I might go mad in the pursuit."

I don't know about this idea of the self that is somehow separate from the functionality of the mind, but my therapist seems to think that's a thing. I grew up being praised for being smart and I've always valued it, to the point that the functionality of my mind has been a core part of how I view who I am in the world. If the Lexapro is working, and I think it is, that means that the chemicals in the drug are adjusting the chemicals in my mind. An imbalance in the central part of who I am.

And what does it mean for the Lexapro to be working? Wang talks about a friend whose OCD is alleviated after starting Prozac but is still most comfortable when it's tidy. When I mess up, when I say something dumb at work or burn an ingredient I've spent a lot of money on, it's not as if I don't still doubt my value in the world. The Lexapro just gives me a second between when something happens and when my mind starts telling me negative stories about it. But I can live in that space between.

Genna Kohlhardt lives and writes in Denver, Colorado, where she also serves as the workshop programs coordinator at Lighthouse Writers Workshop and co-editor of Goodmorning Menagerie, a chapbook press for experimental poetry and translation.