There are certain books you love and feel like you are coming home whenever you read them again. That’s how I feel about Julia Alvarez’s In the Time of the Butterflies. Although I love the March sisters dearly, they don’t come close to the Mirabal sisters: Dedé, Minerva, María Teresa (Mate), and Patria.

Unlike the sisters and Julia Alvarez, I am not Dominican. I come from a white German farming family, but I instantly recognized the loving and secretive Catholic Mirabals. Growing up, I often floored the gas pedal of our family’s car to try to find something more interesting, just like Minerva: “my foot pressing heavily down on the gas as if speed could set me free.”

Alvarez shows the ways families connect and miss one another—the details they keep secret and the ones they share; how we can never completely know anyone, especially those we love the most. Her novel structure reflects this—three sections with four different narrators. By the end, you realize no family member knows everyone’s thoughts and secrets. Only the reader has that honor, although we are left with Dedé, the survivor, piecing together the death of Minerva, María Teresa and Patria. This honors the writing rule that the reader should know more than the characters, but it also echoes how families work —we often don’t know the whole story. We’re often left to piece together the snippets we are left with.

In the Time of the Butterflies is a coming of age book, a family book, a political book, but of course these are all intertwined. As Julia Alvarez says: “A novel is not, after all, a historical document, but a way to travel through the human heart.” Alvarez uses the larger world context of the Trujillo dictatorship and the ways that people turn on one another for a deeper, high-tension story. But Alvarez also makes her characters complex, even the minor ones. Patria says about Peña, Trujillo’s henchman, he is both “angel and devil, like the rest of us.”

As a young, female writer, this book was essential to me. You could be taken seriously, but still write about family and the minor things in life with a lot of heart, because none of it is minor. It’s what makes life worth living and literature worth reading. So many big, important novels are missing a heart, and this is part of why In the Time of the Butterflies endures. Alvarez skillfully weaves between the personal family story and the larger, dictatorship/political one. Throughout, the novel asks: how do you not betray yourself, but keep yourself safe?

From the beginning of In the Time of the Butterflies, Alvarez shows the weight of being a survivor through Dedé, the only sister who survived, but also through the Dominican Republic as a country, what it endured and the ways its people betrayed each other. Patria, the older sister, says, “Once the goat [Trujillo] was a bad memory in our past, that would be the real revolution we would have to fight: forgiving each other for what we had all let come to pass.”

How do a people forgive each other? We don’t find out until times of greatest pressure what people are made of, and it’s a good reminder for writers to put our main characters into the pressure pot to get to know them better and let them surprise us.

As a younger writer at Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, I was lucky enough to study with Julia Alvarez. She pointed out how my writing needed more one-sentence quick descriptions, and I keep pushing my students to create their own. It speeds up your story’s pace and helps you find depth. Here are some of Alvarez’s wonderful ones:

Trujillo’s wooing Lina Lovaton, Minerva’s friend and classmate at school: “Gifts were sent over to the school…little bottles of perfume that looked like pieces of jewelry and smelled like a rose garden wished it could smell.”

Their nun teacher addressing Minerva and her classmates: “Personal hygiene, she called it. I knew right away it would be about interesting things described in the most uninteresting way.”

About their father, from Minerva: “Right then and there, it hit me harder than his slap: I was much stronger than Papá, Mamá was much stronger. He was the weakest one of all.”

Minerva dancing and talking to Trujillo at a party: “Instantly, I feel ashamed of myself. I see now how easily it happens. You give in on little things, and soon you’re serving in his government, marching in his parades, sleeping in his bed.”

About their neighbor and friend, Don Bernardo: “He spent most of his days reminiscing on his porch and tending to an absence belted into a wheelchair. From some need of his own, Don Bernardo pretended his wife was just under the weather rather then suffering from dementia…Briefly, he entered the bedroom where Dona Belén lay harnessed in her second childhood.”

Maria Teresa in prison hears another person pray: “May I never experience all that it is possible to get used to.”

Patria: “All at once, I lost my home, my husband, my son, my piece of mind…I could hear the babies crying far off and voices calming them and Noris sobbing along with her aunt Mate, and all their grief pulled me back from mine.”

Minerva: “And that’s how I got free. I don’t mean just going to sleepaway school on a train with a trunkful of new things. I mean in my head after I got to Inmaculada and met Sinita and saw what happened to Lina and realized that I’d just left a small cage to go into a bigger one, the size of our whole country.”

When I first read Minerva realizing that Trujillo was instead a dictator and not a kind leader, and that she freed her mind, the only thing she can control, I felt a thrill of excitement. How we do that: the small rebellions when we have so little control. It’s a universal human struggle: if your control is taken away, people struggle to get any piece they can.

So much In the Time of the Butterflies’ tension comes from the reader knowing three of the four sisters are going to die. Alvarez never confuses surprise with suspense. Instead she entrusts her reader so that they can feel the weight and paranoia of living in a dictatorship. You are never truly safe. Never truly free. We feel the danger when Trujillo becomes interested in Minerva’s classmate, then later when he becomes interested in Minerva. We feel the shock of their father’s secret family, and his later arrest. The shock of the arrests: three of the sisters’ husbands, Patria’s son Nelson, and then Mate and Minerva. But what stands out is how well these tensions and scenes build on one other to create an ending that still haunts me a decade after first reading it.

So much of In the Time of the Butterflies can be studied and dissected, but the two pivotal scenes—when Minerva slaps Trujillo when they’re dancing together and then the scene when Rufino, their driver, begins to take the three sisters up the mountain pass they won’t survive are essential for studying plotting. (Time to create a “Building the Unavoidable Scene” craft class, I think.)

Throughout the middle of the novel, the reader feels the impending weight of Trujillo’s man Peña taking over Patria’s house and their community. When we see Peña’s white SUV outside one of Trujillo’s mansions as the sisters are in the car on their way to visit their husbands in prison, we know, as they do, that it’s a death sentence.

And as a reader, once again going to the mountain pass where I know the sisters won’t survive, I felt ill. I made sure I had time, late at night when my kids were asleep, where I could be in the moment, feeling the dread and sorrow. Then I was left with Dedé, trying to piece the tragedy together. This is what the best pieces of literature do: transport us and break our hearts. Just like Dedé says, I felt: “ghosts all around us.”

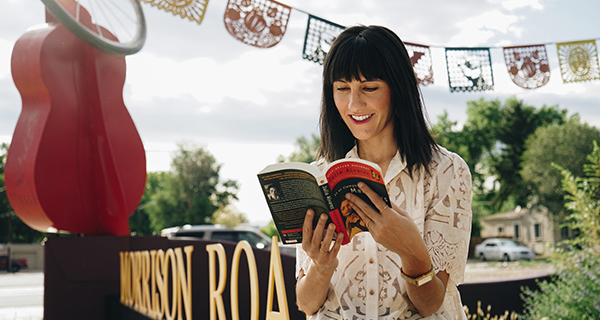

I love all of Julia Alvarez’s books and I’m thrilled her new one, Afterlife, will be published April 2020. But In the Time of the Butterflies is the one that I will always deeply love and come back to again and again, as if visiting beloved family. If you haven’t read it yet, pick it up. You still have time for the NEA Big Read, and to hear the amazing Julia Alvarez speak on Wednesday, November 6 and even teach a craft class on Thursday, November 7. Don’t miss out.

Viva las Mariposas and Julia Alvarez!

Paula Younger received her MFA from the University of Virginia Creative Writing program, where she was awarded a Henry Hoyns Fellowship. She was also the Fiction Editor for Meridian and a Bronx Writers' Center Fellow. Her award-winning fiction has appeared in such literary journals as HarperCollins’ Forty Stories,The Chicago Tribune’s Printers Row Journal, The Rattling Wall, The Southeast Review, Best New Writing, and The Momaya Review. Her nonfiction has appeared in The Nervous Breakdown, The Manifest-Station, and The Georgetown Review. Her novel, Here with the Saints, was one of five finalists for the Virginia Kirkus Literary Award, and has also been a finalist for the William Faulkner-William Wisdom Creative Writing Competition, Santa Fe Writers' Award, and the Dana Award for the Novel. She's also a winner of the Beacon Award for excellence in teaching at Lighthouse.