By Jennifer Wortman

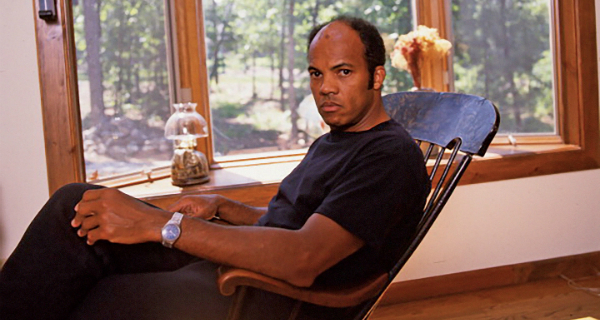

In the short story “Weight” by John Edgar Wideman (pictured above, in the 90's), the narrator is a writer writing about his mother, who dies by the story’s end. He feels complicit in her death, or at least in her suffering; his depiction has reduced her to a strong God-fearing Black woman trope, which he comes to see as a form of erasure. At least, I think that’s what happens. I’ve read “Weight” many times, but I haven’t read it since my father died. I was going to reread it before writing this essay, but I couldn't bring myself to.

When my father was dying, I took notes. I had no artistic agenda, or so I’d like to think. I just wanted to capture him on paper, so he would die less. Once he said, “Are you taking notes for your novel? I don’t want you to write about me.” Before I could remind him that I don’t write novels, my mother burst in. “What are you going to do about it?” she said to him. “Write a bad review?”

Years before my father’s death, I wrote a story about a woman’s strained relationship with her father, a character who’d manifested as a colder, crueler, sadder version of my dad. It was what the story required. That’s what I told myself.

A version of the story with the colder, crueler, sadder father was accepted by a magazine. The magazine held onto it for a couple years then decided not to publish it, paying me a kill fee that far exceeded payment for any story I’d published before. I liked to joke that I should make a career of getting paid not to publish my work. Beneath the bitter humor: relief.

Despite my relief, I couldn’t let that colder, crueler, sadder father story go. Over the course of many years, I rewrote it. It hadn’t been good enough, but I could make it better. I could make the father better. I softened him, but not too much. I added a disastrous love interest for the protagonist and probed her depression. The story got accepted by another magazine.

The colder, crueler, sadder father story came out a few months after my dad was diagnosed with stage four cancer. My parents were busy with the paradoxical work of his dying: trying to prolong his life, then his comfort, while preparing for his death. It wasn’t hard for my story to pass notice, but just in case, I warned my mom to avoid it. I didn’t have to warn my dad: his cancer made it too hard for him to read.

After he died, I realized a part of me had wanted him to read the story, so I could clarify that the father wasn’t him but a colder, crueler, sadder version of him enlisted for fictional aims. I could apologize and explain, to defuse any distress he’d experience while he read it. And to defuse any distress I’d experience while he read it.

Maybe I also wanted him to read it because I’d feared that in response to my story, he’d become that colder, crueler, sadder father, and I needed him to show me otherwise. Despite the fact that as he was dying, he’d become warmer and kinder, if not happier. Yet the only words of his I’ve shared here are gruff: “I don’t want you to write about me.”

Perhaps I’ve shared those words so I can say now what I couldn’t say then: How can I not write about you, Dad? I am small and you are big, you are perfect. You remarkable, confounding, beautiful man: I couldn’t have made you up. I can’t let you go.

I just forced myself to reread “Weight.” I didn’t want to demean the story and Wideman by describing the story incorrectly. The narrator of “Weight” laments demeaning his mother by describing her incorrectly. In his defense, he says, “What's anybody want to hear anyway. Not the truth people want. No-no-no. People want the best told story, the lie that entertains and turns them on.”

I consider Wideman a literary father: I couldn’t write the way I write if not for “Weight.” The story gave me permission to self-interrogate, to innovate, to marry the cerebral with the visceral and the lyric.

“Weight” also gave me permission to explore my suspicion of the creative impulse. Writers like to extol the virtues of writing and reading, for there are many. But I’ll leave the extolling to others, except to say that after my father’s death, my writing saved me. I wielded it like a weapon.

Why do I need a father’s permission to write as I do?

Editor's Note: Lit Counts is an essay series in which readers and writers from our community express why they believe in supporting and elevating literary arts—the mission of Lighthouse Writers Workshop. The series will countdown toward Colorado Gives Day on December 4, the annual statewide fund drive for nonprofits. For 2018, Lighthouse has set a goal of $90,000, to support the continued growth of our literary programs. If you believe in the mission of Lighthouse, consider scheduling your contribution today.

Jennifer Wortman is the author of This. This. This. Is. Love. Love. Love., a short story collection forthcoming from Split Lip Press in spring of 2019. Her fiction, essays, and poetry appear in Glimmer Train, Normal School, DIAGRAM, Hobart, The Collagist, Confrontation, North American Review, PANK, Southeast Review, Okey-Panky, SmokeLong Quarterly, The Collapsar, Juked, and elsewhere. She is an associate fiction editor for Colorado Review.