William Haywood Henderson is both a wise instructor and mindful writer. He has taught at many prestigious schools and has published many incredible books. He's a trusted Lighthouse instructor and Book Project Mentor. He'll be teaching a few classes at this year's Lit Fest, including one on how to tap into your subconscious when writing. He'll also be teaching a two-week intensive on crafting your voice and a craft seminar on finding your personal imprint.

I know you've spent some time in Wyoming growing up, and it has been the primary setting for all three of your novels, so how does your personal experience influence your setting? What is it about Wyoming that draws you back to it again and again as far as your work is concerned?

When I was in college, my parents bought a ranch outside of Dubois, Wyoming. After I graduated from college, I traveled a bit and then thought I’d start my writing career. (Yes, I was young and naïve.) I took on the caretaking of the ranch for a year, alone, through the fall, the amazingly-cold winter, into spring, and the very late arrival of the next summer. Of course, I was too inexperienced to have anything useful to write about, so I spent a lot of time sleeping, crying, listening to the Cars, Adam Ant, and the Sex Pistols (if the solitude wasn’t going the kill me, my playlist was going to try), and wandering the wide-open landscape. It was a six-mile drive down a very bad dirt road to town, so I was alone nearly all of the time. But I got to know some locals, got to learn about the land from people who had lived there their whole lives, and got to feel what it might be like for me if some of the locals learned that I am gay. When I wound up in an MFA program about five years later, I was already writing about a very small figure (somewhat related to me) in a very large, dangerous landscape (Wyoming, where you don’t head out in a vehicle without some survival gear on hand, because you could die if you get stuck or lost). I kept writing stories mostly set in Wyoming, because it turned out that that sense of solitude and danger was elemental to how I felt about myself within society—when living in San Francisco, I’d been threatened with death for walking down the wrong street; my close friends had died of AIDS; and, before and after San Francisco, I often felt that I was not fully part of my own family. As a side note, even though I have three siblings with whom I have close relationships, my protagonists are always only children—another way that the underlying emotion of my life drives my fiction.

What is your strangest writing ritual or routine that you have? How did it come about and how vital is it to your writing process?

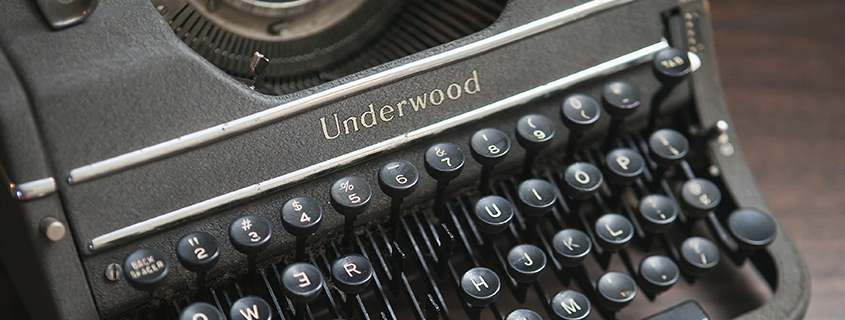

I often write while wearing a gorilla suit and a tiara. No, wait, that was a dream. I don’t know if I have any strange rituals, but I do write mostly longhand, and then transfer the text to a computer, then write the next draft longhand, and on and on. There’s a different, more intimate (and slower, which is good) engagement with the text when you’re shaping it word by word with ink in a beautiful notebook. I also sometimes copy a favorite or particularly appropriate-to-the-moment poem into my notebook or Word file, right in the middle of my text, and there it sits for a while until its beauty or complexity or specific metaphors have etched themselves in my mind, and then I delete the poem and keep writing.

What is the best piece of writing advice you have ever received?

When I had my last one-on-one meeting with my first fiction instructor, Leonard Michaels, at the end of my undergrad career, he said, “Just keep writing.” It might not sound profound, but it sustained me for many years—he was saying “you have something worth exploring.” And in grad school, John Hawkes told me to keep writing about the wilds of the West—he could see that my fiction lost some sort of edge or originality when I took my characters to the city. I’ve followed that advice for my whole career. To translate these bits of advice to someone else, I might say that you should dig in and keep going, and that you should find what is most original about your sense of self and the world.

On a similar note, as a teacher and mentor, what is a piece of writing advice you are always giving out?

I talk a lot about drafting, how long it takes, how it’s only after a few (ten? twelve? fifty?) drafts that a piece of writing has the density and complexity to begin to work on all levels. I also talk about keeping the dramatic thread going across scene and chapter breaks—it’s hard to do, but it’s what makes a story coherent. But to me, the most important part of learning to write and write well is to break out of all the restrictions we put on ourselves—we don’t want to embarrass ourselves, we don’t want to hurt our characters, we want to appear to be wise and magnanimous, we want to sell a million copies, and we want our fellow workshoppers to say nice things about our efforts. Little (none?) of that is likely to get anyone anywhere useful. Your task is to create the work of art that only you can create—literally, only you know what you know, have experienced your very particular slice of the world, and only you speak and see through your personal lens. We all get held up by our fears and our ideas of what writing should be. I work to help students see what their particular writing should be, which might be influenced by other writers (it has to be) but is ultimately as individual as a fingerprint. At Lit Fest this year, I’m teaching a two-weekend workshop called “Modulation—Your Voice and the Secrets of How to Use It.” The most important word in that title is “your”; you dig around until you find what makes your voice unique, and then you lean into it.

And finally, I must know, is your next book going to be set in Wyoming?

I’ve been working on my current novel since 1894 (or that’s what it feels like). It was once the story of a relatively-minor character from my novel Augusta Locke, her childhood in northern California, and her eventual move to Wyoming to live with her great-grandmother Gussie Locke. So, yet again, Wyoming played a vital role in the novel. But I dropped Wyoming from the novel about halfway through the drafting process, and now the protagonist is male instead of female. But landscape and location still play a huge part in the story. It takes place in Stinson Beach and the Point Reyes Peninsula, a remote corner of the world north of San Francisco, where you’re at the mercy of earthquakes and fog. Yeah, fog isn’t going to kill you, but it definitely tests your sense of the world and what you might run into around the next bend.

William Haywood Henderson earned a BA in English from the University of California at Berkeley, an MA in creative writing from Brown University, and attended Stanford University as a Wallace Stegner Fellow in Creative Writing. He is the author of three novels: Native, The Rest of the Earth, and Augusta Locke. He has taught creative writing at Brown, Harvard, the University of Denver, the University of Colorado at Denver, and Ashland University. At Lighthouse, he directs the Book Project and teaches the Advanced Novel Workshop and the Novel Bootcamp.