So often, we fiction writers project a reader who is lazy, listless, or passive—who has to be seduced. This can give our storytelling a frantic quality. We’re always trying so damn hard.

I think that’s why, when I sit down to write, a malaise sometimes comes over me. What’s the point of this game? What is fiction for? Truth is more terrible than fiction, the world is threatening to burn, and here I am trying to engineer a right to be heard.

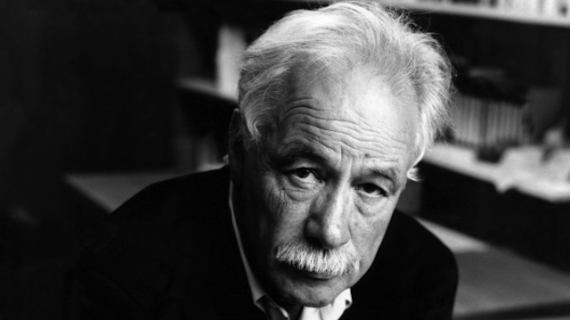

The best remedy I’ve found is reading—reading, specifically, the work of W.G. Sebald, and for the following reasons:

- Voice: Sebald writes fiction as if he is writing memoir or nonfiction. No self-conscious quirkiness here, no portentous affect, no sense that every line needs to be a laugh line, no sense that the author is working overtime to make us “care.” His narrators describe something they’ve seen, something they’ve read, somebody they’ve met, with the matter-of-factness of people telling a story they know is important. They know it is important because they know it is true, and because they know one true thing inevitably connects to other true things going on in the world, and because they trust the reader to know this too.

- Structure: In place of the conventional elements of narrative structure—character’s “desire,” the external or internal antagonist, and the rising will-she-or-won’t-she action of Freytag’s triangle—Sebald gives us a patterning of images and events that resonate back and forth across the narrative. Structurally speaking, Sebald’s fictions are poetry.

- Character: Sebald grants his protagonists absolute dignity. We see concrete evidence of neuroses at work, we see how wars and other injustices have deformed their lives. But they are always spoken of with a grave respect. The narratives show suffering without seeming to speak for anyone and without in any way diminishing the sufferers; there’s no condescension and no irritation in these portraits.

- Spirit: Some novelists write about the paradoxes of memory, time, and loss. Sebald evokes the experience of those paradoxes. The first time I read Austerlitz, I actually experienced the spookiness of a distant memory that suddenly surges into the present, bracketing and changing the meaning of everything that has been happening in the recent past.

- Politics: A challenge for fiction writers who want to engage with political matters is that their writing will take on the prime characteristic of political discourse: lack of nuance, the reduction of truth to formula. The glancing, echoing way in which Sebald’s narratives introduce world-historical events models a different possibility.

Lighthouse instructor Rebecca Berg will be teaching Reading as a Writer: W.G. Sebald’s Austerlitz starting July 6. Berg holds a Ph.D. in English literature from Cornell, and her fiction has appeared in Five Fingers Review, Four Way Review, and Stillpoint Arts Quarterly, among others.