by Lynn Wagner

I can still remember a Saturday morning craft class with Ilya Kaminsky that I attended eight years ago-- one of those beautiful classes where you spend much time listening to a brilliant writer read and notice master poems.

The most astonishing assignment Kaminsky gave us was to ‘write a translation’ from an Alexander Bok or Anna Akhmatova poem. That’s not too tough a task for Kaminsky, a Russian immigrant, but what of the rest of us?

The whole point, of course, was to use what we had—five or six translations to English, a prose trot, hearing the original in Russian, and to sit down and make choices. It’s what writers, and, doubly so, translators do.

Here’s Evening, an early poem by Anna Akhmatova, translated by Judith Hemschmeyer

Here’s Evening, an early poem by Anna Akhmatova, translated by Judith Hemschmeyer

He loved three things in life:

Evensong, white peacocks

And old maps of America,

He hated it when children cried,

He hated tea with raspberry jam

And women’s hysterics.

. . . And I was his wife.

And the same from Stanley Kunitz:

Three things enchanted him:

White peacocks, evensong,

And faded maps of America,

He couldn’t stand bawling brats,

Or raspberry jam with his tea,

Or womanish hysteria.

. . . And he was tied to me.

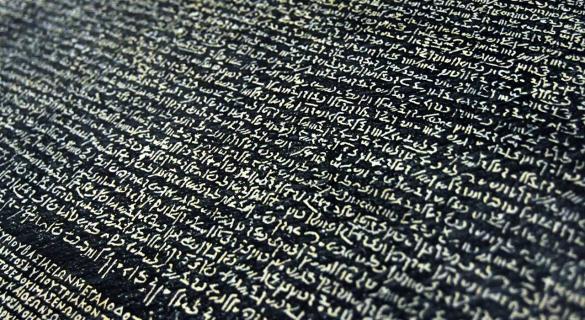

Seven lines, 37 or 35 words: either the children cried or they were bawling brats. In translation we can revisit and decide: rhythm, diction, syntax, tone. It’s one of the joys of reading poems from other times, languages and cultures. In a Paul Celan poem, which I use for my title, language almost disintegrates.

The power of words, however, never disappears. After reading Zbigniew Herbert & Tomas Tranströmer, Marina Tsvetaeva & Wislawa Szymborska, we'll do the same with the next paired poets in translation, June 11 at Lit Fest with Paul Celan and Anna Akhmatova. Join me.

And for the fiction take on writers in translation, see Rebecca Berg's Harness the World: Works in Translation That Will Transform Your Writing on June 10.