By Joy Roulier Sawyer

I first encountered Vassar Miller’s poetry more than twenty years ago, while paging through an anthology in a fusty used bookstore. I’d never heard of her. Yet after reading only a few poems, I knew I would purchase every book she’d ever written. Miller is a master of formal verse: sonnets and double sestinas brimming with imagery, word play, effortless and barely imperceptible rhyme. Like Gerard Manley Hopkins’s crammed-with-life poetry, her words are packed so tightly together the crackling energy is visceral, physical.

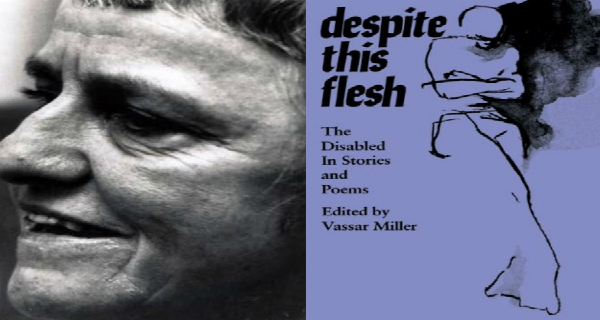

Though her work is still largely unknown, Miller was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in the sixties and twice Texas Poet Laureate, her work respected by well-known poets and acerbic critics. Over the years, the more of her poetry I read, the more I am soul-stunned into silence.

Her 22-sonnet cycle, “Love’s Bitten Tongue,” is a tour de force: more than three times the length of a traditional sonnet crown. Awed by her feat, I once attempted my own cycle—and stopped short at eight sonnets. Many years later, I wrote a poetry book, Tongues of Men and Angels, consisting of almost entirely formal verse, and I included that eight-sonnet sequence.

In honor of the poem that first inspired me to venture beyond free verse, the book’s epigraph is from sonnet 10 of Miller’s “Love’s Bitten Tongue.” It is the only sonnet that mentions the title.

There’s yet another reason I find her poetry remarkable, one I discovered when I first read her collected poems, If I Had Wheels or Love (Southern Methodist University Press). In “Subterfuge,” she writes:

I remember my father, slight,

staggering in with his Underwood,

bearing it in his arms like an awkward bouquet

for his spastic child who sits down

on the floor, one knee on the frame

of the typewriter, and holding her left wrist

with her right hand, in that precision known

to the crippled, pecks at the keys

with a sparrow’s preoccupation.

The poet had cerebral palsy, and throughout the course of her life, she typed her hundreds of poems—and her brilliant sonnet cycle—with one finger.

Miller’s work possesses a sunny audacity, poems that paint delightful pictures of imagined strolls through squishy mud, poke raucous fun of patronizing people, pay fond tribute to beloved friends.

Yet there’s another side to her poetry: she grieves the absence of romantic love, the desert of her unexpressed sexuality. Her Christian faith is genuine and dark: she argues with God, rails against hypocrisy, refuses to gloss over the wrongdoings of others.

In reviewing one of her books, the novelist Larry McMurtry says that, “one of the things that writers do is to turn pain into honey for their readers. No pain, no honey.” He writes of a very particular kind of pain portrayed in Miller’s poetry—that of people not understanding that the very thing that caused her the most suffering, her disability, was also the thing most resplendent for her with poetic possibility.

In “For a Spiritual Mentor,” she writes:

May I not be like those who spit out life

Because they loathe the taste, the smell, the muss

Of happiness mixed with the herb of grief.

Throughout her poetry, Miller holds happiness and grief in tension. The result is honey. The poet romps across the page with unabashed joy: “…all stubby legs / puppies and kittens tumble, living Easter eggs.” Yet her pain is raw: “I wish I could call my mother / or eat death like candy.”

In the preface to Miller’s collected poems, George Garrett writes: “I have no doubt at all that somewhere there is a very young person, maybe even an unformed poet, who will sooner or later pick up this book and read in it and be moved and changed for good.”

I felt as if he was talking directly to me. And I felt I couldn’t pass up the opportunity had to tell the poet herself how fortunate I was to discover her, how her poetry had affected my life and work.

So I wrote her. I told her what I still tell others today: when in need of inspiration, I read Vassar Miller. When discouraged about the lonely vocation of poetry, I read Vassar Miller. When tempted to be petty or overwhelmed by private sorrow, I read Vassar Miller.

I soon received an enthusiastic letter from the poet, telling me she was working on poems, a novel, and a play, and that she was doing well. I jotted her a quick note, told her I was glad she was having such a fruitful season, that I was looking forward to reading more of her work. She passed away shortly after our exchange.

Years ago, when Miller was inducted into the Texas Women’s Hall of Fame, the poet Shaun Griffin was standing next to then Governor George W. Bush onstage when it came time for her award.

Says Griffin, “Vassar looked radiant that evening, and if she could not go to the podium like the other women, she stilled the room with her diminutive frame. The governor was overtaken with emotion and did not know what to do, so he handed me her award…. He was effaced and without instruction; she was surrounded by her friends and waiting for his hands.”

Sometimes, in her written presence, my soul falls silent and still, too. And that is literature’s power: it expresses what simply cannot be spoken—not just by Vassar Miller, but by me. There are, and always will be, emotions and memories and flights of imagination beyond my ability to voice aloud.

Like Vassar Miller, it is only through writing, through the love of literature, that my bitten tongue is loosened.

Editor's Note: Lit Counts is an essay series in which readers and writers from our community express why they believe in supporting and elevating literary arts—the mission of Lighthouse Writers Workshop. The series will countdown toward Colorado Gives Day on December 4, the annual statewide fund drive for nonprofits. For 2018, Lighthouse has set a goal of $90,000, to support the continued growth of our literary programs. If you believe in the mission of Lighthouse, consider scheduling your contribution today.

Joy Roulier Sawyer holds an MA from New York University, where she received the Herbert Rubin Award for Outstanding Creative Writing. The author of several nonfiction books, she's also published two poetry collections, Tongues of Men and Angels (White Violet Press), and Lifeguards (Conundrum Press), and is a recent Pushcart Prize nominee. Joy's poetry, essays, and fiction appear in Books & Culture, LIGHT Quarterly, Lilliput Review, Mars Hill Review, New York Quarterly, St. Petersburg Review, Theology Today, and others. In addition, she also holds a master's degree in counseling, and her professional training in writing therapy gives her special interest and expertise in writer's block, writing exercises, and the writing process. For her longtime work in the field, Joy received the 2013 Distinguished Service Award from the National Association for Poetry Therapy.